Colonialism and Planning in the Peel Watershed

Written by Admin, Admin •

Hi all, program coordinator Dali Carmichael here! With the Yukon’s Peel Watershed in the news again, I revisited a paper I wrote about the precedent-setting Supreme Court case during my time in York University’s Masters in Environmental Studies program. This was written a year after the court’s decision came down in favour of the Na-Cho Nyak Dun, fellow appellants, and modern treaties. To learn about the ongoing case, check out this article from Yukon News: FNNND argues Yukon breached its’ constitutional duty to implement Treaty promises

The Peel Watershed Regional Land Use Plan should have been a successful endeavour. It was predicated on the concepts of collaborative planning, conservation, and economic development. It had buy-in from almost all if its proponents – that is, until the Government of the Yukon dramatically shifted the course of the project.

Project background

One of the defining elements of the modern Yukon policy regime, and of the Constitution Act, 1982, is that it includes mechanisms to ensure that the First Nations and Inuit populations have a say on matters that may impact their traditional territories, treaty lands and cultural activities.

At the territorial level, this mechanism can be found in an Umbrella Final Agreement (UFA) ratified in 1993 by the Government of Canada, the Government of the Yukon and the Yukon First Nations (Government of Canada, The Council for Yukon Indians and The Government of Yukon, 1990). This non-legally binding document established a framework for the parties to use in their negotiations as they concluded a series of individual final agreements with the 14 Indigenous nations of the Yukon, who are also unified under the Council of Yukon First Nations (Council of Yukon First Nations, 2018, p. 4).

Chapter 11 of the UFA clearly stipulates specific land use planning processes for settlement and non-settlement lands, to be used in planning processes outside community boundaries, subdivisions, local planning areas and national parks (Council of Yukon First Nations, 2018, p. 26). These processes were to be followed as the territorial government began establishing land use plans for each of its nine identified planning regions (Government of Canada, The Council for Yukon Indians and The Government of Yukon, 1993).

Maher, P. for Clynes, T. (2014) Yukon Government Opens Vast Wilderness to Mining. National Geographic. Retrieved from https://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/01/140124-canada-yukon-peel-watershed-wilderness-mining-first-nations/

It is important for Indigenous populations of the Yukon (and beyond) to be decision makers in land use planning processes, foremost because it is their right as the original inhabitants and stewards of the land. Many nations possess unique knowledges and relationships with place established over millenia that inform their approaches to planning and development, while simultaneously conserving and working within natural systems.

Aftab and Hemphill state that Indigenous planning requires processes that are in tune with those relationships, and that are sensitive to nuanced local differences (Aftab & Hemphill, 2013, p. 19). They also state that it is essential that any “Indigenizing role” in planning is filled by a local community planner, “…who carries the local culture in his or her bones” (2013, p.19).

To reciprocate, the non-Indigenous professional planner’s role in any kind of “decolonizing” process on Indigenous lands, they suggest, is to challenge existing power relations, to work in a manner that respects local views and voices, and to conduct themselves in a way that is culturally appropriate and relevant at any moment in the planning process (2013, p. 19).

Following devolution in 2003 (CBC News, 2016), when the federal government bestowed the Yukon Government with provincial powers, it initiated regional planning processes for the Peel Region. As required the under the UFA, the plan was prepared by a body of representatives from the Yukon Government, as well as First Nations with traditional claim to the land (Government of Canada et al, 1990). The Peel Watershed Planning Commission was made up of six public members nominated by the Na-cho Nyak Dun; the Gwich’in Tribal Council; a joint Yukon Government/Vuntut Gwitchin nominee; a joint Yukon Government/Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in nominee; and two Yukon Government nominees (Peel Watershed Planning Commission, 2011).

It took several years of discussion, but ultimately the commission was able to put forth a plan in 2011 that most parties agreed to (CBC News, 2011).

Maher, P. for Clynes, T. (2014) Yukon Government Opens Vast Wilderness to Mining. National Geographic. Retrieved from https://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/01/140124-canada-yukon-peel-watershed-wilderness-mining-first-nations/

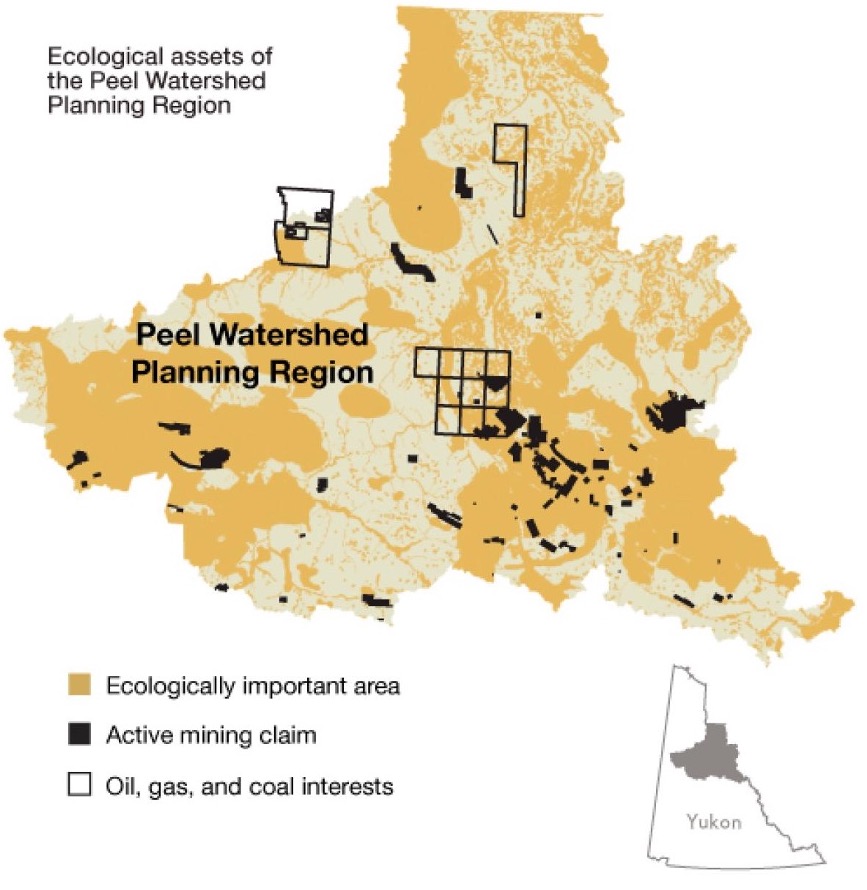

The Peel Watershed is one of the northernmost planning regions within the Yukon. It is 67,431 square km – roughly the size of New Brunswick (Peel Watershed Planning Commission, 2011, p.2). It encompasses numerous tributaries and mountain ranges, borders the Northwest Territories, and is home to mineral, gas and oil developments (Peel Watershed Planning Commission, 2011).

The final recommended plan for non-settlement land released by the Peel Watershed Planning Commission in 2011 proposed specific land uses – namely, that 80 per cent of the region was to be made up of conservation areas, including special management areas (55 per cent of the region) and wilderness areas (25 per cent of the region). Though existing oil, gas, and mineral claims were allowed to remain, no new transportation routes would be allowed to be built across conservation areas.

Additionally, under this regional plan, 20 per cent of the land mass was determined to be “integrated management areas,” where new oil, gas, and mineral claims would be allowed, subject to regulatory processes (Peel Watershed Planning Commission, 2011, p. 3). These areas would be composed of three sub-categories divided into zones. Zone II would allow for low levels of industrial development and access; Zone III would allow for conservative levels of industrial development and access; and Zone IV would allow for higher levels of industrial development and access. (Documentation noted that numbering begins with Zone II to be consistent with the North Yukon Regional Land Use Plan.)

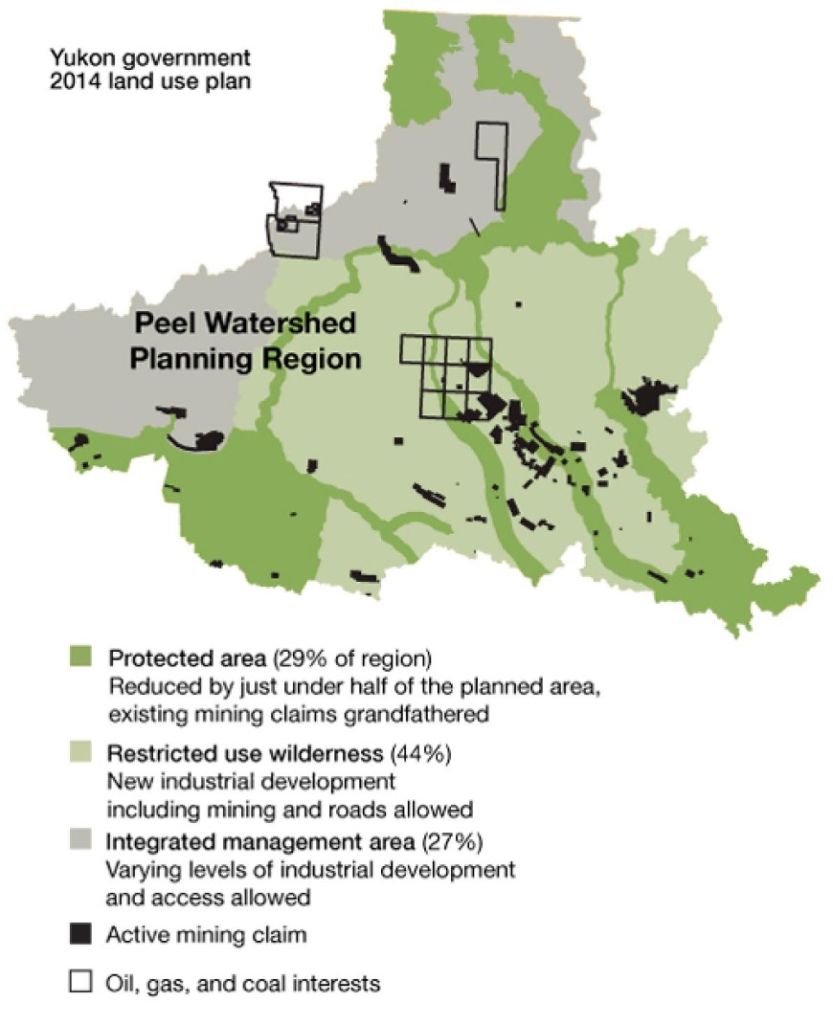

In January 2014, the Government of Yukon revealed a significantly different Peel Watershed Regional Land Use Plan for non-settlement land (Stantec). This plan zoned 29 per cent of the region as protected areas; 44 per cent as restricted use wilderness areas that allowing for low levels of managed land use activity in the form of resource development; and 27 per cent as integrated management areas, where most land use activities and resource development activity could occur. This plan opened up 71 per cent of the Peel Region to development, a far cry from the 80 per cent conservation areas promoted in the Commission’ plan.

The problem

The plan proposed by the Yukon Government abandoned the framework laid out in the UFA that respects the need for Indigenous planning processes. Instead, it favoured primitive accumulation (Roy, 2006, p. 14), while claiming to espouse principles outlined in communicative planning methods (Sager, 2009, p. 67) and collaborative dialogue (Innes & Booher, 2010, p. 4)

It is not unusual for colonial governments to gloss over the wants and needs of Indigenous peoples to implement their own plans. As Aftab and Hemphill state:

“…planning has been an apparatus of colonization in Canada and much of the New World. Every parcel of land in our country belonged to Indigenous people at one point. After colonization, Indigenous people were placed on reserves where familiar planning tools were [mis]used for their subjugation. On top of this, the profession denied the existence of an ancient Indigenous planning tradition. The political, legal and bureaucratic exercises of power were based in a racist and paternalistic attitude: that “I”—the non-native, expert planner know better than “you”—and should therefore be in charge.”

(Aftab and Hemphill, 2013, p. 18).

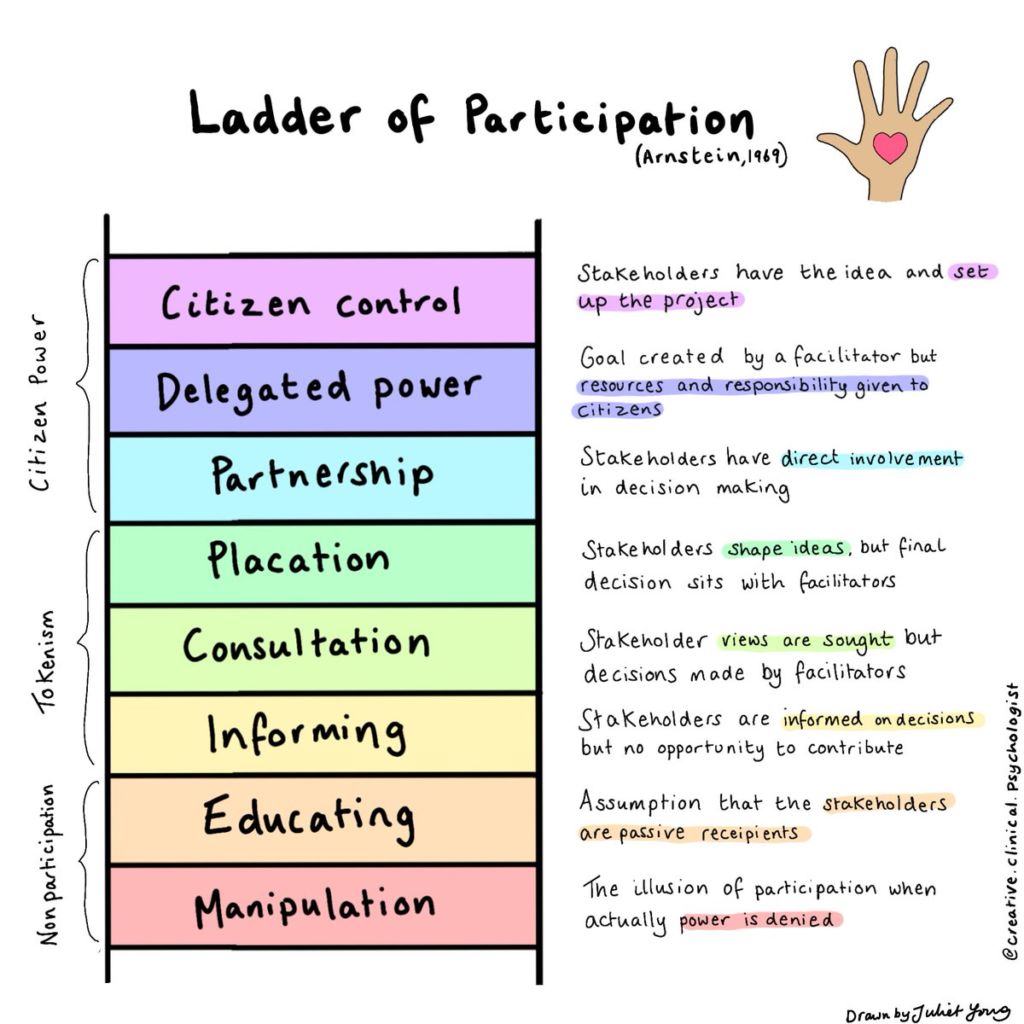

Until this point in the Yukon’s planning process, it might have measured high on Arnstein’s Ladder of Participation in terms of local involvement (Arnstein, 1969). Because the First Nations were involved in the development of the plan from its inception, with regular opportunities to offer input, I believe it would have been placed on a high rung of partnership or delegated control. As soon as the Government of the Yukon announced its plan, it barely registered on the ladder, unilaterally removing the power of local advocates despite agreeing not to do just that.

The actions by the Yukon government demonstrate the pitfalls of primitive accumulation and sometimes violent or unpleasant ways in which neoliberal development proceeds to accumulate capital (Roy, 2006, p. 14). By putting economic development over the needs and wants of the Indigenous nations – who were willing to compromise and act in good faith – the Yukon government ignored the due process that it itself had put in place, and in doing so, cheapened the processes of democracy itself, using its power to marginalize the opinions of an already marginalized population (Manning, 2012, p. 361).

Outraged by the methods the government had used to undermine them, the First Nations filed a lawsuit against the Yukon, alleging the territory did not have the authority under the UFA or any other Final Agreement to make the changes it had made (Supreme Court Judgements, 2017). Yukon Government had provided very general suggestions at an early stage of planning, only to follow up with a proposal that disregarded much of the Commission’s plan. The case was precedent setting, as it was the first test of a modern treaty in the Supreme Court of Canada (Jaremko, 2017).

The actions of the Yukon also sparked outrage from local conservation organizations and environmental activists, who then collaborated the Indigenous nations to #ProtectthePeel (CBC News, 2012).

After three years in the court system a Supreme Court ruling landed on December 1, 2017, declaring that while the terms of the UFA were not legally binding, the Crown was found to have breached “its obligation in respect of a joint process established under a modern treaty” (Supreme Court Judgements, 2017).

The judge also quashed the Yukon’s final land use plan and ordered the planners to go back to the drawing board, from the point in time at which Yukon came to engage in final consultation with the First Nations.

Additionally, the Yukon decided to halt a second regional land use plan until this one was settled in court. There has been little development on that plan since.

At this point in time, a new commission is in the process of being created, with a new territorial government involved in the planning process. I believe the first plan submitted by the original commission should have been enacted. Through democratic processes, it better met needs and wants of the majority while still making space for both economic development and conservation opportunities.

REFERENCES

Arnstein, S. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4) p. 216–224.

Aftab E. and Hemphill, J (2013). “Indigenizing and decolonizing: An alliance story”. Plan Canada 53(2). Retrieved from http://uturn2.cyansolutions.com/cip/plancanada/summer2013/811AAFADF66AC2F41C6986D3A4917F4A/PC_2013_Q2_BookPRINT.pdf

Beneria, L. (2016). Development as If All People Mattered in Gender, Development and Globalization: Economics as if People Mattered. London and New York: Routledge.

CBC News. (2011). Peel watershed commission issues final report. CBC. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/peel-watershed-commission-issues-final-report-1.1046699

CBC News. (2012). Groups disappointed in Yukon government’s plan. CBC. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/groups-disappointed-in-yukon-government-s-peel-plan-1.1154074.

CBC News. (2016). Federal gov’t ordered to negotiate over Taku River Tlingit’s Yukon land claims. CBC. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/taku-river-tlingit-yukon-land-claim-supreme-court-1.3429574

Clynes, T. (2014) Yukon Government Opens Vast Wilderness to Mining. National Geographic. Retrieved from https://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/01/140124-canada-yukon-peel-watershed-wilderness-mining-first-nations/

Collier, P. (2010). The Political Economy of Natural Resources. Social Research, 77(4), p. 1105-1132. ISSN: 0037-783X. Retrieved from http://web.a.ebscohost.com/ehost/detail/detail?vid=2&sid=d2790bd7-8406-42e5-a27d-fa70e30ec5c7%40sdc-v-sessmgr02&bdata=JnNpdGU9ZWhvc3QtbGl2ZQ%3d%3d#db=bth&AN=59533916

Council of Yukon First Nations. (2018). An Understanding of the Umbrella Final Agreement. Retrieved from https://cyfn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/ufa-understanding.pdf

Government of Canada, The Council for Yukon Indians and The Government of Yukon. (1990.) Umbrella Agreement. Retrieved from https://cyfn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/umbrella-final-agreement.pdf

Government of Yukon. (2014). Government of Yukon approves land use plan for public lands in Peel Watershed region. Retrieved from http://www.gov.yk.ca/news/14-011.html

Jaremko, S.L. (2017). The Peel Watershed Case: Implications for Aboriginal Consultation and Land Use Planning in Alberta. Canadian Institute of Resources Law. Retrieved from https://cirl.ca/files/cirl/the-peel-watershed-case_jaremko.pdf

Kawaja, C. & Tukker, P. (2017) Sustainability and Indigenous Interests in Regional Land Use Planning: Case Study of the Peel Watershed Process in Yukon, Canada. CBC. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/peel-watershed-scoc-appeal-yukon-liberal-government-1.3943091.

Manning Thomas, J. (2012). Social Justice as Responsible Practice: Influence of Race, Ethnicity, and the Civil Rights Era” in Sanyal, B. et. al., (Eds). Planning Ideas That Matter: Livability, Territoriality, Governance, and Reflective Practice. Cambridge, MA: MIT

Peel Watershed Planning Commission. (2011). Highlights: Final Recommended Peel Watershed Regional Land Use Plan. Retrieved from https://planyukon.ca/index.php/documents-and-downloads/peel-watershed-planning-commission-documents/plans/frpwlup/373-highlights-of-the-final-recommended-peel-watershed-land-use-plan/file

Porter, L. (2006). Planning in (post) colonial settings: Challenges for theory and practice. Planning Theory & Practice, 7(4), 383-396.

Ross, M. (1999). The Political Economy of the Resource Curse. World Politics, 51(2), 297-322. doi:10.1017/S0043887100008200

Roy, A. (2006). Praxis in the Time of Empire. Planning Theory. 5(1), p. 7-29.

Supreme Court Judgements. (2017). First Nation of Nacho Nyak Dun v. Yukon. Retrieved from https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/16890/index.do

Tobin, C. (2014). The spirit of the land claim was betrayed: court. Whitehorse Daily Star. Retrieved from https://www.whitehorsestar.com/News/the-spirit-of-the-land-claim-was-betrayed-court

Tukker, P. (2017). Supreme Court’s Peel decision ‘a victory for democracy,’ First Nations say. CBC. Retrieved from https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/north/supreme-court-decision-peel-watershed-premier-reaction-1.4428732

Watson, P. (2012). Hungry miners covet Yukon’s pristine watershed wilderness. Toronto Star. Retrieved from https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2012/04/15/hungry_miners_covet_yukons_pristine_peel_watershed_wilderness.html

Ward, S. (2010). “Transnational Planners in a Postcolonial World” in P. Healey and R. Upton (eds.), Crossing Borders: International Exchange and Planning Practices. New York: Routledge, pp. 47-72.