The Holland Marsh: A CHL Under Threat?

Written by Admin, Admin •

Ahh, the dreaded Hwy 400. It’s always under construction and, despite this, drivers tend to lean hard on the gas pedal as they speed towards some rural destination. Throw in a few fighting kids and maybe a dog with car sickness, and the journey can be unpleasant to say the least.

Then, you round a bend and descend into a valley. Traffic slows as you and the other travellers collectively adjust to the snaking stretch of road ahead. Your knuckles get some colour back as you relax your grip, taking in the hypnotic rows of bright yellow canola and other produce as they melt into a forested hill in the distance.

You’ve reached the Holland Marsh.

I’ve always felt a sense of relief hitting this milestone. When making the trip from city to country, the Holland Marsh is not only a navigational resource – no matter where I land it seems to mark the halfway point to my destination – but it also breaks up the scenery. Past this point, agrarian lands fade into Canadian Shield and the typical “northern” aesthetic, with more coniferous trees and less open land.

What I didn’t realize, and what I assume many other drivers may not realize, is that this corner of the province has been a haven for wayfinders since time immemorial. The Holland Marsh, which includes a section called the Holland Landing, has a storied history as a major northern traffic junction and a place of human activity for over 12,000 years.

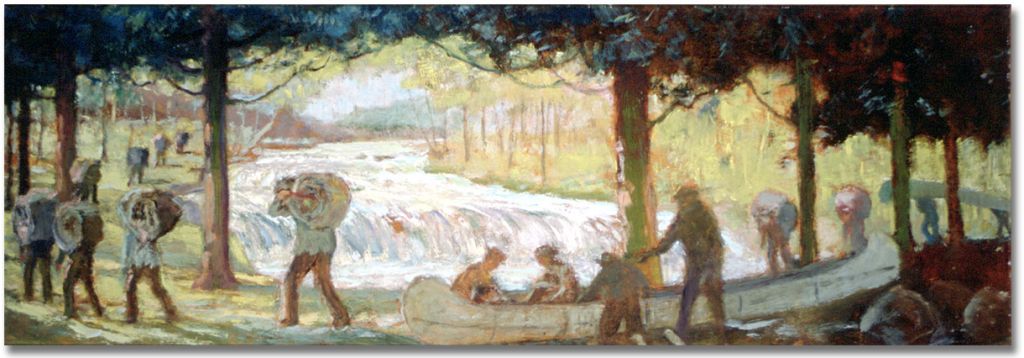

Bert Duclos, a former heritage outreach consultant with the Ontario Ministry of Culture, wrote this excellent letter summarizing the history of the junction. Many Algonquian and Iroquoian-speaking peoples have, at one point or another, lived along the banks of the river and have their own names for it: Escoyondy to the Chippewa and Miciaguean to the Mississaugas. Likewise, settler explorers began navigating the Holland River in the 1600’s, bestowing their own colonial names along the way. The fingers of the waterway extend from west to east, an aquatic freeway crossing major bodies of water and connecting the farthest reaches of the northern Great Lakes to the iconic Mississippi Delta.

Progress or paving paradise?

In September 2020 the provincial government of Ontario announced it was starting a Preliminary Design Update Study in an effort to revive the Bradford Bypass, also known as the Holland Marsh Highway, originally approved in 2002 by a Progressive Conservative provincial government. This new 16-kilometer stretch of road would connect Hwy 400 to the 404, running directly through the Holland Marsh and potentially easing congestion in a region slated for population growth.

Just over a year later, in October 2021, the Ontario government announced its decision to exempt the proposed highway from the province’s Environmental Assessment Act, though a previous assessment was approved in 2002 with 15 conditions. Despite these approvals, the project was shelved in the early 2000s by an incoming Liberal government, and officially scrapped when it was left out of the Places to Grow Act in 2005.

A comment submitted to the province regarding the Bypass by C. William D. Foster, a community activist when the highway project was first explored, called the original assessment’s legitimacy into question based on a procedural issue. Upon completing a Freedom of Information (FOI) request, Foster found a condition for project approval that compelled the proponent to report to the Ministry of Transportation (MTO) every two years regarding the “status and scheduling of the overall undertaking, design studies, and construction projects including the anticipated date of completion.” The last time this condition was met, according to the FOI documents cited by Foster, was in 2008.

In addition to eliciting concerns about environmental impacts on the marsh itself and on one of Ontario’s most fruitful pockets of agriculture, it is unclear how much support local First Nations and Métis communities have for the Bypass.

In a detailed article about the Holland Marsh and the history of the Bradford Bypass, journalist Joel Wittnebel noted that in a recent presentation to York Regional council, officials from MTO said they consulted with the Williams Treaties First Nations, the Huron-Wendat Nation, and the Mississaugas of Scugog First Nation. However, he added, the extent and procedure of the consultation was not “explained and no documentation of the First Nations’ position was shared.”

A MTO report to the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada filed in February of 2021 stated that it would be engaging and consulting with the Métis Nation of Ontario (MNO) Georgian Bay Métis Council, the Huron-Wendat Nation (regarding archaeological resources only) and Alderville, Beausoleil, Chippewas of Georgina Island, Curve Lake, Chippewas of Rama, Mississaugas of Scugog Island, Mississaugas of the Credit, and Hiawatha First Nations.

In recently submitted comments to the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada, the Huron-Wendat Nation (HWN) expressed its sacred obligation to “ensure respect for and protection of our archaeological and burial sites,” and that they were “very concerned” about the Bradford Bypass, supporting a request from Ecojustice to designate the project under the legislation.

…it poses real risks to the integrity and protection of such sites, and, most worryingly, poses real risks to the undisturbed repose of our ancestors’ remains.”

Remy Vincent, Grand Chief of the Huron-Wendat Nation

Hiawatha First Nation also expressed its objection to the Bypass development over concerns about the high potential of destroying significant wetlands and archaeological sites belonging to First Nations, including burial and other sacred sites.

“We feel there would be significant cultural loss,” wrote Tom Cowie, a land and resources consultation officer for the nation.

When the provincial government initially attempted to get the Bypass built in the late 1990s, the Chippewas of Georgina Island First Nation wrote that they strongly opposed it, not in principle, but because of its location. Foster’s background documentation includes two letters dating back to 1998 from Rob Porte, who was working with Georgina Island’s cultural portfolio at the time.

“This site was critical and instrumental to the formation of Canada and one of the contributing factors which brought our people to take up a permanent settlement on Lake Simcoe’s south shore,” he wrote in the first letter, adding that the “value of this place cannot be underestimated.”

It is not our intention to impede progress, however, we do not want to see a significant piece of history such as this lost forever. Not only is the camp a home of our forefathers, but given the Nomadic nature of the times, and the length of time this site was used, there will undoubtedly be burial grounds in this area.

Rob Porte, Cultural Portfolio, Georgina Island Council, July 1998

First Nations’ knowledge about the historical value of the Holland Landing is well substantiated by archaeological science. An Executive Summary of Stage 3 Test Excavation of the East Holland River prepared by New Directions Archaeology in 2006 recommended that given the “obvious significance of this site,” it would require Stage 4 mitigation including excavation or avoidance, or a combination of the two. The report further emphasized that excavation of the site would have to be done by hand, with each of 8,000 one-metre square portions sifted through six-millimetre mesh netting by hand.

What could make archaeologists assert such an extreme opinion, requiring so many resources? Stage three testing conducted on roughly one per cent of the East Holland River site in 2004 revealed almost 4,000 artifacts, described in the table below.

| Category | Total Artefacts | Description |

|---|---|---|

| All | 3943 | -Stage 3 testing was conducted across roughly 1% of the East Holland River site in 2004 -97 test squares were completed over a 60 x 220 metre site |

| Prehistoric (pre-dating the 19th Century) | 3672 | -Mostly ceramic sherds, chipped lithic tools (including 13 temporally diagnostic projectile points) and debitage (waste flakes from stone tool production) -5 ground stone tool fragments were also recovered -803 calcined bone fragments were recovered. Some may prove to be historic rather than prehistoric |

| Historic (19th Century and beyond) | 271 | -Mostly ceramics, glass, and kaolin/ball pipe -Also many miscellaneous metals and gun flint |

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY OF STAGE 3 TEST EXCAVATION OF THE EAST HOLLAND RIVER SITE

NEW DIRECTIONS ARCHAEOLOGY, 2006

“A significant number of person years would be required to complete the analysis and reporting for this site,” New Directions concludes.

Are alternative routes enough?

In April 2021, the government announced changes to the route of the Bypass, stating that it would lessen the development’s impact on the Holland River and avoid an archeological site.

Will this adjustment satisfy the concerns of those against disturbing the historically, culturally rich peat of the Holland Landing? Porte’s second letter representing the sentiments of the Chippewas of Georgina Island to MTO makes it seem unlikely.

“Georgina Island is opposed to any construction or development or including road construction and archaeological digs at the site known as Lower Holland Landing,” he wrote in 1998. “We will continue to be opposed to anything that disturbs or destroys this ancient place.”

It appears that someone may have suggested to Porte that the nation call for the Holland Landing to be designated as a Cultural Heritage Landscape under the Historical Sites Monuments Board. At this time, the federal body was exploring inclusive approaches to preserving Indigenous historic sites that placed less importance on its scientific or archaeological aspects, and more emphasis on the cultural value to Indigenous nations with contemporary and historical ties to the place.

While the intention behind these shifts may be good—rerouting the highway to avoid specific locations, harnessing colonial mechanisms to protect Indigenous cultural sites—they may not be convincing enough to eliminate or accommodate community concerns around cultural loss. In both cases it’s possible that early and sustained collaboration between colonial governance and Indigenous Nations could have led to better outcomes for all involved.

“My reason not to call for a designation by Historical Sites Monuments Board [sic] is that these people may dig-up this site and open it up like a tourist attraction,” Porte wrote. “This place must remain undisturbed. I assure you we will be opposed to this as long as it is considered an option.”